Biocontrol

Hypovirulence

For over 40 years, researchers have attempted to control the severity of chestnut blight cankers by way of infecting the chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) with viruses that reduce its virulence. Blight cankers that result when C. parasitica is virus-infected are often large and swollen, but allow the tree to fight infection. This method of biocontrol, called “hypovirulence,” has been shown to be most effective at keeping American chestnut trees alive and healthy when individual cankers are treated consistently for several years.

Strains of the chestnut blight fungus must be genetically compatible in order for them to fuse and share genetic material, including hypoviruses. Genetic incompatibilities between C. parastica strains hinder the natural spread of hypoviruses such that a hypovirulent blight infection cannot necessarily spread and protect other trees in the same orchard or woodlot.

Researchers at the University of Maryland have created “super donor” strains of the chestnut blight fungus by deleting genes at six locations in fungus genome that prevent the spread of viruses (learn more here). The USDA is currently evaluating whether or not to continue to regulate the release of super donor strains of C. parasitica. Meanwhile, researchers at the University of West Virginia are evaluating methods to keep American chestnut trees alive and healthy by treating individual blight cankers with the super donor.

TACF’s primary application of hypovirulence is to keep individual American chestnut trees alive for use in breeding. Currently, hypovirulence is not a feasible method for large-scale American chestnut restoration due to the limited natural spread of hypovirulent strains C. parasitica, including the super donor strains.

Figure 1: Example of a hypovirulent chestnut blight cankers

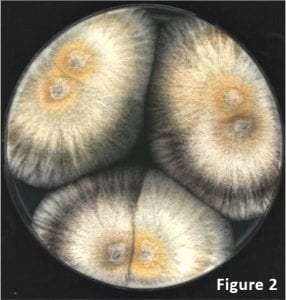

Figure 2: Petri dish with six genetic strains of the chestnut blight fungus

Figure 3: Chestnut blight cankers are often swollen after “mudpacking” to introduce competing microorganisms from the soil into cankers

When viruses infect the chestnut blight fungus, the fungus changes color from orange (virulent) to white (hypovirulent). There are six genetic strains of the chestnut blight fungus growing in the petri dish pictured above in Figure 2. The compatible strains are growing together and transmitting hypoviruses, while the incompatible strains do not merge and transmit viruses.

Mudpacking

Mudpacking refers to applying compresses of forest soil to blight cankers to introduce micro-organisms that compete with Cryphonectria parasitica. The cankers that develop after mupacking are often swollen. We use mudpacking as an alternative to hypovirulence to prolong the life of American chestnuts for use in breeding.