About Us

The Virginia Chapter of The American Chestnut Foundation is actively engaged in efforts to bring the American chestnut back to Virginia’s forests. Here you will find information about our past and present activities, how they contribute to fulfilling our mission and answers to some of the questions you may have about American chestnuts and our breeding programs.

Our Mission

The mission of the Virginia Chapter of The American Chestnut Foundation is to restore the American chestnut tree to Virginia’s woodlands to benefit our environment, our wildlife, and our society.

Donate to the Virginia Chapter

Make a one-time donation to support our restoration activities or schedule monthly donation to sustain our continuing operations.

Become a Sustaining Donor

Become a sustaining donor by putting us in your will, estate plans, or donating land for a breeding orchard. Without people like you, The American Chestnut Foundation wouldn’t exist as it does today.

The Chestnut Story

The American chestnut was once one of the most important trees in our eastern hardwood forests. It ranged from Maine to Georgia, and west to the prairies of Indiana and Illinois. It grew mixed with other species, often making up 25 percent of the hardwood forest. In the virgin forests of the Appalachian Mountains, the ridges were often pure chestnut. Mature trees could be 600 years old and average 4 to 5 feet in diameter and 80 to 100 feet tall. Specimens as large as 8 to10 feet in diameter were recorded.

The American chestnut’s annual production of highly nutritious nuts was extremely reliable. At the turn of the 20th century it was ranked as one of the most important wildlife plants in the East. Many wildlife species depended extensively on them. Bear, deer, wild turkey, squirrels, many birds and small mammals – and once, the huge flocks of passenger pigeons – all waxed fat for the winter in the chestnut forests.

Eastern rural economies depended on the nuts as well. Livestock were fattened on them, and the nuts were a major cash crop for many families in Appalachia. Railroad cars full were shipped to the big cities for the holidays, because of the high demand for this finest-flavored of all chestnuts.

The tree was also one of the best for timber. It grew straight and tall, often branch-free for 50 feet. Loggers tell of loading entire railroad cars with boards cut from just one tree. Straight-grained, lighter in weight than oak and more easily worked, it was as rot-resistant as redwood. It was used for virtually everything – telegraph poles, railroad ties, heavy construction, shingles, paneling, fine furniture, musical instruments, even pulp and plywood.

Then the chestnut blight struck. First discovered in 1904 in New York City, the lethal fungus–an Asian organism to which our native chestnuts had very little resistance–spread quickly. By 1950, except for the shrub-like sprouts the species continually produces (and which also usually become infected), the American chestnut had virtually disappeared from eastern forests. In Virginia, trees that have survived the blight are few and far between. While those that have survived are truly a beautiful sight to behold, they are disappearing quickly.

Multiple efforts are underway to bring this precious tree back. Recent developments in genetics and plant pathology promise that this magnificent tree will again become part of our natural heritage. The American Chestnut Foundation was created to coordinate a breeding program for the purpose of creating blight-resistant American chestnuts for eventual reforestation. TACF scientists are well on their way to developing a tree that is American in every way, with blight resistance borrowed from its Asian cousins. Virginia is one of several states that now have satellite breeding programs to ensure that blight-resistant trees will be suited to local environments.

Blight-resistant seeds and seedlings will not be available to the public for several more years. Meanwhile, individuals and organizations concerned about issues such as forest diversity and wildlife preservation are encouraged to plant chestnut seedlings that are not blight-resistant, for several reasons. First, planting seedlings is an important way to help preserve the chestnut genes that we might otherwise lose. It will also help call attention to the effort to bring back the tree. Also, by planting these seedlings, individuals and organizations gain knowledge about where and how to plant and care for chestnuts, in preparation for the widespread efforts that will be necessary once blight-resistant seeds and seedlings are available. Finally, it is important to note that if there are no blighted chestnut trees within a mile of where new seedlings are planted, blight is not likely to occur in the new trees for 10 to 20 years (20 to 40 feet of growth). Individual trees that do become blighted can be treated if the blight is caught and treated quickly.

Chapter History

The Virginia chapter of TACF was formed in 2006. Of course, Virginia is in the heart of chestnut country and has been at the center of the restoration effort from the beginning. The national research facility is located in Meadowview, in southwest Virginia, and scientists at Virginia Tech have been involved in chestnut research since long before there was a state chapter. The formation of the Virginia chapter kicked off the effort to develop a tree specifically adapted to the climates and soils of the northern part of the Commonwealth. The chapter office opened in Marshall in 2008 to provide a convenient place for meetings and volunteer training programs.

The Virginia chapter shares a Regional Science Coordinator with the Kentucky, Maryland and West Virginia chapters. The Regional Science Coordinator is the liaison among the chapters and with the national organization and oversees the breeding program in the state. The Regional Science Coordinator for Virginia is Brianna Heath. He can be contacted at his office in the Virginia Department of Forestry offices:

900 Natural Resources Drive

Charlottesville, VA 22901

Cell (828) 450-9100

A Southwest Virginia Branch of the chapter focuses on activities in and around Meadowview. Contact information for the branch is:

29010 Hawthorne Drive

Meadowview, VA 24361

(276) 944-4631

A Catawba Valley Branch conducts activities in the Roanoke and Blacksburg areas.

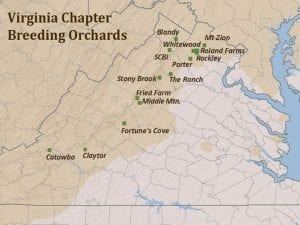

The first two Virginia chapter chestnut breeding orchards were established in 2007. There are now 14orchards, including two with only pure American trees to be used for future breeding and research. Our goal is to have at least one breeding orchard in each county west of the fall line and north of Roanoke.

As of 2017, Virginia’s chestnut breeding program has expanded to 14 orchards, two with pure American trees, at the locations shown.

Our Newsletter - The Bur

The Virginia Chapter’s semi-annual newsletter, The Bur, contains important stories about the progress we are making in our programs of planting and breeding American and hybrid chestnut trees in orchards and forests throughout the state.

Copies of The Bur can be downloaded in pdf format from the links below.

Download Issues of The Bur

Fall 2021

Spring 2021

Fall 2020

Spring 2020

Fall 2019

Spring 2019

Fall 2018

Spring 2018

Fall 2017

Spring 2017

Fall 2016

Spring 2016

Fall 2015

Spring 2014

Fall 2013

Spring 2013

Spring 2012

Fall 2011

Fall 2010

Spring 2010

Fall 2009

Spring 2009

Spring 2008

Fall 2007

Board of Directors

The Virginia Chapter’s Officers and Board of Directors are drawn from throughout the state’s regions.

John A.Scrivani, PhD, President

Fred V. Hebard, PhD, Vice-President

Tom Wild, Secretary

Cindy Ingram, Treasurer

Darrell Blakenship

Steven Bodolay

Clem Carter

Jerre Creighton

Jack Lamonica

Bob Lawrence

Warren Laws

Beth Merz

Rob Porter

Anna Sproul-Latimer

Ed Stoots

Rod Walker

Pete West

Virginia Chapter Menu

Latest News

Fall 2021 Newsletter Has Many Interesting Articles!

The Fall 2021 issue of The Bur, the Virginia Chapter's semi-annual newsletter, contains many interesting updates on our progress toward reestablishing the American chestnut to our forests. You can download it here. .

Spring Issue of The Bur Published

The Spring 2021 issue of The Bur is now available for downloading as a pdf file. This 12-page issue is packed with exciting news about our progress in re-establishing the American chestnut.

Fall Issue of The Bur Available

The Fall 2020 issue of the Virginia Chapter's newsletter, The Bur, is now available for downloading.